In spite of myself I find the Christian story compelling. Or is it truer to say the Jesus story? At some level, anyway. Because often I just get unstuck and stumble against an aspect of something I can’t put my finger on. Is it dogmatism? Theological rivalry? The leveling of "heretic!" from many sides?

"I imagine God is weary of being called down on both sides of an argument."

Charles Frazier, Cold Mountain

I don’t know. All I do know is that there’s something there that keeps me exploring it.

See, on the nondual side of things, the crisp and rigorous Dzogchen expository view, for example, invites us to experientially enter the perfect and definitive clarity of what is. Here, there's no 'revelation' to have faith in, no semantic riddles to decipher. It’s the perfectly lucid and verifiable description of true nature — the nature, truth, and experience of the of singular consciousness and appearance of the ‘dream’.

"In the vast expanse of the ultimate nature, there is no time, no identity, no duality, no striving, no delusion, and no realization. Everything is spontaneously present, free from effort, like the sky naturally open and spacious. To realize this is to rest in the effortless expanse of the true nature, beyond hope and fear, beyond grasping and rejecting. This is the great perfection."

Longchenpa - The Precious Treasury of the Dharmadhatu

But the biblical narrative, it seems to me, is something else. Perhaps it’s the story of how the great dream unfolds — God's great cosmic drama. There be spoilers!

It’s the syncretist (or the perennialist?) in me that wants to smush the two (or more) approaches together, treat them as complementary, and take them as one. But also I'm looking to see if they both speak of and meet at the ‘same place’.

It's perhaps notable that my awakening came through explicitly nondual traditions, teachings, and practices. I really didn’t have much to do with the Bible in my seeking days. But since then, I've found something in it which fascinates — particularly the mystics and contemplatives. No surprise there.

Among the great variety of Christian thought and theology that I've explored, a universalist, theosis-centered understanding makes the most sense to me. Anything less than “God, all in all” — such as annihilationism or infernalism—seem perverse and absurd in light of God’s cosmic, boundless, loving nature.

Bottom line, it’s the abiding realization of and identification with the ineffable that's the ‘goal’ of all this. In the East, it's called enlightenment (and many other names signifying fundamental unity/oneness). In Orthodoxy, it’s called theosis. In Catholicism, it’s called divinization. I think Protestants have a more fundamentally dualistic telos. But I’m open to being corrected on that front.

But I’ll quote Meister Eckhart here because I think he’s right on the money:

"Theologians may quarrel, but the mystics of the world speak the same language."

How to Spot the Ineffable

If you want to be a contemplative, then contemplate. Not by hoping for or imagining some future cloistered life, but now, as the desire arises by grace. The wish is the invitation. Redeem it here and now.

Sometimes one might use some spiritual text to promote a silent reverie, à la Lectio Divina. I’d say that the same or similar approach can be found in centering prayer. In that case, a single signifying word is chosen to represent one's intention to assent to the divine work in one’s soul, to 'catalyze' the non-grasping spaciousness of the ground of our being. Experientially, both ways become springboards into the divine 'mood' of the contemplative state.

There’s something ecstatic about all this, too. And I’m not sure it’s so present in the nondualists per se. Bliss, sure; ecstasy, not so much. The bhaktis? Hell yeah. But the risk there — as indeed is mentioned in The Cloud of Unkowing but applies to devotional practice in general — is in constructing a kind of forced and artificial emotionalism rather than responding to the authentic presence of grace.

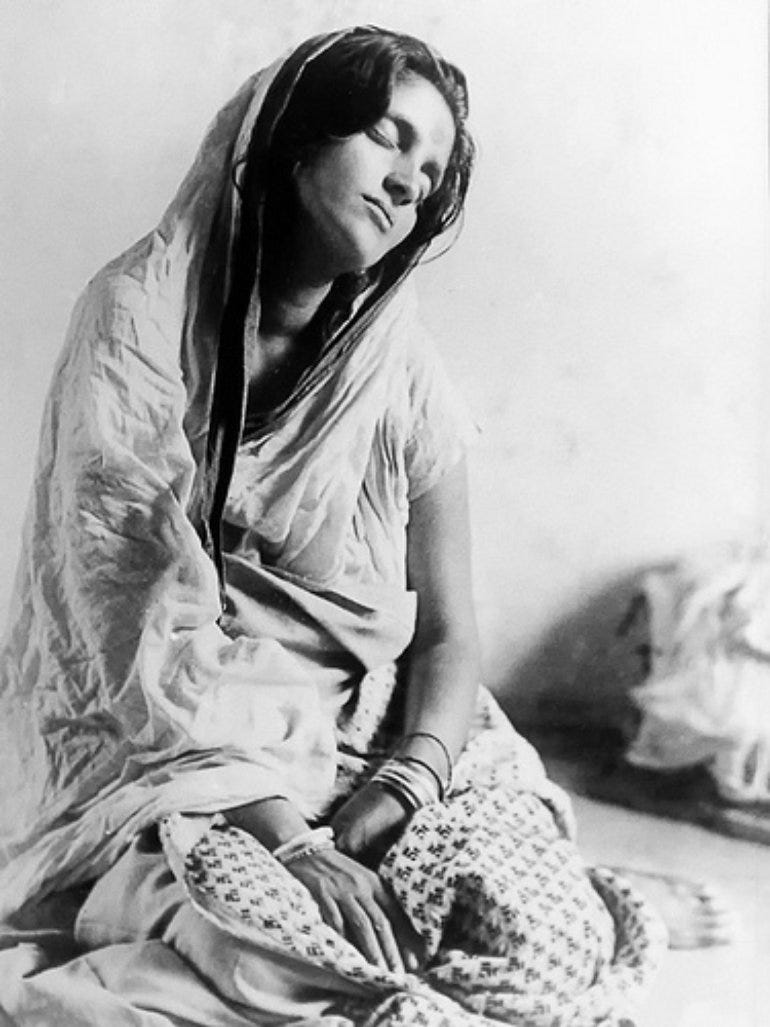

For the true face of bliss and divine ecstasy, one only has to look at a picture of the Blessed Saint Anandamayi Ma. Note that there's no lotus position or rigid upright spine. No formalism whatsoever — just the obvious rapture of an enlightened being in blissful divine union. In fact, the transmission from Ma’s (and other saints) images can itself be used to sympathetically evoke the Divine blissful mood in oneself.

Contemplation practice can be like sitting by a campfire and gently capturing a spark, kindling it into an inner blaze of bliss. This is contemplation and meditation beyond formalism. Sitting quietly, patiently, and reverently doing nothing, we begin to notice these sparks. But even beyond the contemplative space, as we go about our daily lives, these sparks can be spotted in our experience if we’re attentive to them.

Sometimes these "calling sparks" can show up as discomfort or even affliction because we haven’t sufficiently attended to their presence. "God is a jealous God." When He calls us to jump, we say, "How high?" When called inward, we ask, "How deep?"

The mystic calling can be challenging like that. Ramakrishna would often spontaneously collapse into a state of ecstatic devotional bliss. In that condition, he would be unavailable and unheeding of the outer world. Saint Teresa’s mystic sojourns would be so demanding on her that she prayed to God to lessen them — even though she ultimately surrendered to God’s will, recognizing these mystical states were divine gifts meant for her spiritual good.

Point is, embarking on the mystic or contemplative way can be challenging. Sometimes in the most unexpected and beautiful ways. One has therefore to make room for it — ultimately one must prioritize it, arrange one’s life around it, for God, for Truth.

Who is ready for that?

"Seek the highest first." — Ramana Maharshi

"Seek first the kingdom of God." — Matthew 6:33